Brother De Cordova, one of the founders of The Gleaner, in 1874, noted the obligations laid on Masons: “All religion of a denominational character is strictly forbidden, equally with political matters, so that men of all creeds, but who shall believe in the Supreme Jehovah, and men of all shades of politics, shall be enabled to meet on the broad platform of the Craft as one…”

While the Book of Constitutions, published, 1723, stated that Masonic candidates had to be “good and true men, freeborn and of a mature and discreet age, no Bondmen, no women, no immoral or scandalous men, but of good report”. After emancipation, the words “free man” were substituted for “free born” so that from 1847, former slaves could become Freemasons.

Past District Grand Master Afeef Lazarus, versed in Masonic lore, was, fortunately, also familiar with Ranston’s success as author of Behind the Scenes at King’s House, Belisario Sketches of Character, The Lindo Legacy, They Call Me Teacher: The Life and Times of Sir Howard Cooke, and more. Given the commission, Ranston enlisted her husband, Dennis, to design the book.

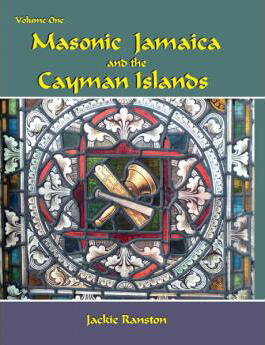

The Third Degree working tools of a Master Mason, photographed from a stained-glass window in the Kingston Parish Church, creates a splendid book cover and highlights the installation of a Masonic Corner in 1891 to honour Brother Dr Robert Hamilton, without doubt the most learned and distinguished Freemason in Jamaica, whose life comprises an entire chapter.

AFRICAN HERITAGE

My own education in Jamaican culture is oriented to our African heritage, but never have I gained a greater perspective on what life among the merchant and governing peoples was like than through the individual histories provided in this book. Those who might wish to leave their estates or money to black or coloured family were forced to use subterfuge when thwarted by other planters. Ranston mentions the story of a Mason’s wife shunned for allegedly sleeping with black men. The husband is granted a divorce, only to have the Privy Council overturn it with instructions that the Local Assembly must never again make such a ruling!

Ranston’s marvellous selection of vocabulary and well-researched quotes make the book read like a celebrity diary. She notes that “Jamaica served as an arms depot for the revolutionary forces when two Kingston Freemasons, Wellwood and Maxwell Hyslop, financed the campaigns of SimÛn BolÌvar, the Liberator, to whom six Latin American Republics owe their independence”. BolÌvar himself was a Mason, enjoying contacts with Brethren in Spain, England, France, and Venezuela until after gaining power in Venezuela, he prohibited all societies in 1828 and included the Freemasons.

The story of Brother Robert Osborn and Brother Edward Jordan, both coloured Masons who worked on behalf of emancipation, makes intriguing reading, as does that of Brother Dr Alexander Fiddes, doctor to the poor, whose testimony on behalf of George William Gordon was ignored. Ranston’s descriptions of the Morant Bay Rebellion, of the Revolution in St Domingue, and of the Ten Years War are compellingly lucid.

Ranston used every source from The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture; The New York Public Library; the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London; The Library and Museum of Freemasonry, London; The National Portrait Gallery, London; the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; the National Museum Kingston to Private Collections belonging to the Sharpe family; the Marquis of Sligo; the Facey/Boswell Trust, Jamaica, and more.

Not being a Mason, I simply ignored all the titles and Lodge names that might be of interest to members and just enjoyed a good read. As Lalor said: “I was glued to it. I couldn’t put it down from the point of view of the history of the Caribbean.”

Source: Jamaica Gleaner